Welcome back, friends! Before this weekend’s penultimate episode (deep, calming breaths), I had an opportunity to sit down with my friend and fellow Outlander fan, Dr. Dori Koehler. I met Dori through multiple Facebook groups in the fandom, and it became quickly obvious that she shared my passion for episode analysis and deeper discussion…aka “geeking out” on Outlander.

Dori has an academic background in history, psychology, and mythology and her blog, mythicbliss.wordpress.com, discusses Outlander through those lenses. I’ve been meaning to pick Dori’s brain for the past few years, and this month I finally got the opportunity. As it goes with such things, we found ourselves discussing things we hadn’t initially intended to, and our exchange of ideas ended up spinning in a variety of interesting directions. So, what follows is the first part in a three part series about which I’m very excited. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did.

Part One: History vs. Historical Fiction and Objectivity vs. Subjectivity

Outcandour: I am so excited to have this discussion with you! I feel like I know you already, being in several Outlander fan groups together, but I’d love to get to know you a bit more before we get started.

Mythscholar: I am a third generation Californian of Azorean Portuguese and Frisian Dutch heritage. My grandparents spoke our native languages and still have ties [to our European heritage]. I grew up in the San Joaquin Valley in an agricultural town called Los Baños. My father is a farmer, and my mother runs the financial end of the farm.

Outcandour: I didn’t realize you grew up in Los Baños! That’s pretty close to my neck of the woods. I know a few veterinary colleagues that do dairy and other large animal medicine in that area. How does a farmer’s daughter from the Central Valley find her way to mythological studies?

Mythscholar: From an early age, I was obsessed with storytelling, reading, theater, television, and film. I started putting on plays in my bedroom with friends when I was about eight years old. I always loved historical fiction, but it was always emphasis on the fiction part. Fiction was my entrance into history.

I received my bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Westmont College in 1999. In mid-2006, I discovered Pacifica Graduate Institute’s Mythological Studies program. The program brings together literary analysis with cultural studies, religious studies, media studies, and political analysis through the theories and methods of Jungian/depth psychology. I jumped in immediately after I found the program. In 2009, I completed my MA, and in 2012, I completed my PhD. My focus has been and continues to be on American popular culture, with particular emphasis in Disney Studies and the way fiction in media reflect American psychological and spiritual realities.

Outcandour: I loved to put on plays, too! Except I would employ my stuffed animals as fellow actors…Care Bears are quite versatile! You mentioned that fiction was/is your entrance into history. How so?

Mythscholar: Oh man, I love the Care Bears. I was also quite partial to The Smurfs. To be honest though, I just loved storytelling in general, especially fiction. Fictional stories are what make me want to learn about history. As this is my orientating perspective, I don’t often have a problem holding the tension between history and fiction. Never have, never will.

Outcandour: I’m very much the same way. I think a lot of people explore a particular history or moment in history after reading fiction. It’s certainly true in the Outlander fandom; Diana Gabaldon has been rightly credited with renewing interest in Scottish history. Regarding the tension between history and fiction, where do you feel that exists the most? Do you think it comes from fellow historians, fiction readers, or both?

Mythscholar: I’d say the tension comes most largely from historians, and rightly so. As an academic lens, History has more in common with the lenses of the social sciences than it does with the humanities. There is a lot of room for speculation and wonder in historical analysis, to be sure, but it’s definitely true that historians have the goal of objectivity in their approach to story. As such, it can be difficult for historians to set aside their epistemological desires as they engage with historical fiction. Again, and rightly so. Quality historical work sees through propaganda. Historians sensitive to propaganda are therefore skeptical of stories that offer alternative versions of history; I’ve often heard historians use varying forms of the adage “the facts are much more interesting.”

Likewise, I’ve also seen audiences become disillusioned when they realize that a historical tale has been embellished or retold in a film or television show. Braveheart is a great example of that. There are several historical divergences in that one, the Battle of Stirling is just one notable example. Viewers can feel taken advantage of if a story is sold as history but is more heavily a fiction than a history. Perhaps that is because there is a default perspective in our culture that stories need to be factual in order to be useful. I’m not sure that’s true, but in the case of historical fiction, that’s certainly an important line to hold.

Outcandour: A comment you made on Facebook has really stayed with me, so I hope it’s not too weird if I quote you to yourself. You wrote, “When we create story, we create perspective.” Would you mind elaborating on that a bit? How does that relate to objectivity versus subjectivity in how we tell and interpret stories?

Mythscholar: It’s not weird at all that you quoted me to me. LOL My comment “When we create story, we create perspective” reflects the truth that all story is someone’s perspective. From my perspective, there is no such thing as true objectivity, only the continued striving for it.

Outcandour: “The continued striving for objectivity” feels similar to what we aim for in the natural sciences—the continued striving for factual data. Are the concepts related?

Mythscholar: Yes, the entire concept of objectivity in academic analysis comes out of late Renaissance/Early Enlightenment thinking from an attempt to get theology out of biological sciences (a project I can DEFINITELY respect; you ALWAYS need to check your biases). But discussions of objectivity versus subjectivity in the world of literary and theatrical analysis didn’t really arise until later. And, in fact, the separation of disciplines into the four lenses we have today (natural sciences, social sciences, history, and humanities) is a relatively modern idea. It comes out of a discussion of the different methodologies and hermeneutical lenses that are employed in different types of analysis.

Outcandour: Okay, I admit I had to look up the meaning of hermeneutical. So, hermeneutics is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially of Biblical or philosophical texts. It reminds me of a conversation I had with Terry and Jayme of Outlander Soul a few years ago, where we discussed exegesis (a “reading out” of a text with what the original author meant to convey) versus eisegesis (“reading into” a text what the interpreter or reader wishes to find). So, I guess most simplistically, we can think of exegesis as “objectivity” and eisegesis as “subjectivity.”

But, unless the original author is still alive, it seems that exegesis could so easily be conflated with eisegesis. And, even when an author is still alive, that objectivity seems like it could still be very fluid; authors can many years later amend or annotate their texts, stories, or characters. J.K. Rowling, for example, has done this with her novels. Do you think we can reconcile those concepts when we discuss history and historical fiction? How do you think it relates to Outlander?

Mythscholar: That’s exactly it. Our hermeneutic is our lens, or perspective. It’s similar to Einstein’s theory of relativity—you begin with your set of givens, and those givens will change depending on where you’re standing at any given moment.

In Episode 305 [Freedom & Whisky] Roger tells Brianna about the stories the Reverend told him about his biological father. He quips that knowing his father helped him know himself and notes that “everyone needs a history.” Brianna asks Roger, “How do you know it’s true? What if he made it up just to make you feel better?” Roger asks her if it matters (which suggests to me that Roger is part philosopher and part historian). Brianna responds with, “But that’s my point! What is history? It’s just a story. It changes depending on who is telling it, like Paul Revere, like Bonnie Prince Charlies, like my parents, like my own. History can’t be trusted.”

But it’s only true that our stories can’t be trusted if we start from the perspective that only facts can be trusted. That gets to the heart of your question about subjectivity versus objectivity. Of course, we value objective facts. But even in hard sciences, where data is key, we recognize that the fuller our picture the better our knowledge. Sometimes we must admit that new information has come to light that shifts what we thought we knew in terms of facts.

The same is true about historical inquiry as well. The more we learn, the fuller the picture we get about the time, place, and the people who experienced a thing. To me, these two things—objectivity and subjectivity— are complementary rather than in conflict with each other.

Outcandour: You are so right— Roger is more of a philosopher than a historian at heart!

Mythscholar: It’s also proven later by his analysis of famous last words in Season Five. He’s more interested in how what our words say about our deeds than the deeds themselves. It’s an interdisciplinary crossover between philosophy, mythology, theology, and history that he seems interested in during this scene.

Outcandour: Maybe that’s why he was so drawn to ministry? The best sermons I’ve ever listened to were interesting mixes of theology, philosophy, and history. I think I’m having a revelation about this character, thanks to you!

Going back to historical fiction and objectivity versus subjectivity, how do you think the idea of “creating story creates perspective” relates to Outlander?

Mythscholar: Outlander is a work of fiction, not a work of history. It employs characters from history, but it is not in and of itself a work of history. As such, it does not need to operate in the world of historical fact. I mean, how could it? It’s a story about time travelers, which as far as we know are fiction. It also employs a fair amount of romanticism—of Scotland and of the American colonies—in its narrative. It’s also a work of fiction by a woman, who although she doesn’t claim the title of feminist loudly, is clearly the recipient of the social progress made by second wave feminism. [Diana Gabaldon] draws on historical facts in her work, but she also tells her story her way.

A good example of this is the way she made many her central characters Catholic. Jamie, Claire, Frank, Brianna, Ian, Jenny…all those families and some of the Ardsmuir men are Catholic. Is it impossible that these people could have been Catholic? No. However, given what we know about percentages of families in the Highlands at the time, it is unlikely that so many of them would have been, especially prominent Frasers and MacKenzies. The same is true of Claire and Frank although, based on the Beauchamp family history in England, it’s slightly more likely. My point is this: Diana begins with her own perspective as a Catholic herself and weaves the story around it. The creation of any story starts with the perspective of the person creating the story. It starts with a perspective, a point of view.

Outcandour: Earlier you said that the fuller understanding we have about a time or place shifts what we previously held as historical fact. This reminds me of the discourse that happened around the show The Spanish Princess a few years ago. The showrunners really made an effort to tell the stories of people of color who existed in Tudor England. But, because so little has been shown in our media about those stories, many were quick to accuse the show of “wokeness” rather than consider that we’ve only been told a white history of the era— people didn’t want to unpack that what they thought were facts was actually a specific perspective.

Mythscholar: Oof, isn’t that the truth. I heard that argument around The Spanish Princess. And, I agree with you. That is utter nonsense. This is why so many of us are calling for broader representation in media. In her wonderful TED talk on stereotypes, The Danger of a Single Story, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie notes that the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue. The problem with stereotypes is that they are incomplete. They lack perspective. They lack the perspective of the person(s) who are the subject of the stereotypes. In analysis of story, we reach a fuller truth by getting different perspectives on the same story.

Outcandour: And isn’t that what we all ultimately want when we approach any medium—a fuller truth? Heck, isn’t that what we want out of life? I really feel like we need minister, historian, and newly-recognized philosopher Roger MacKenzie in here to help us out here, LOL.

Readers, thank you for sticking with us if you’ve made it this far! Next week we take our discussion a bit further, looking at mythology, history, and whether the two can ever be fully separated (hint: we don’t think so).

Slàinte

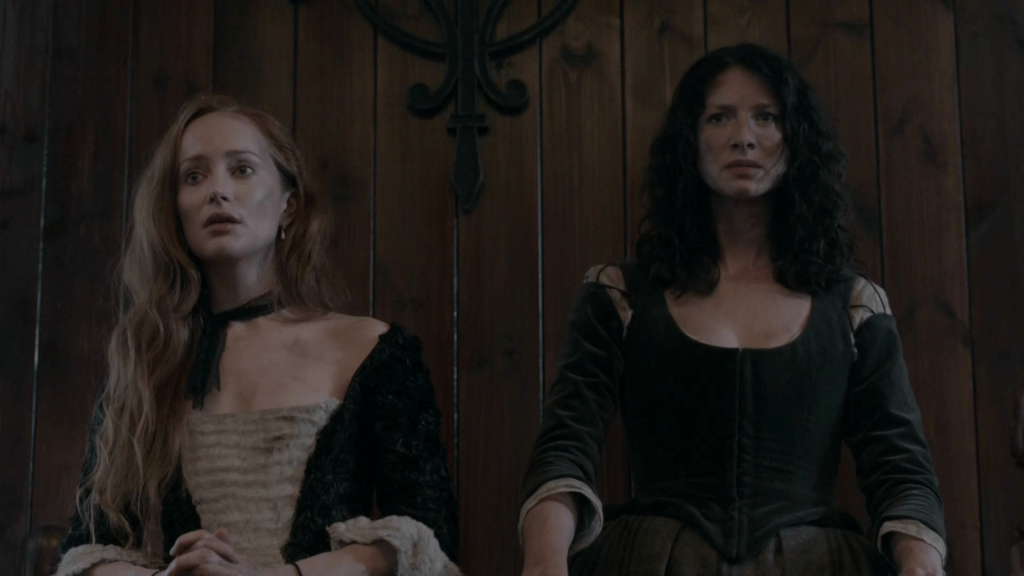

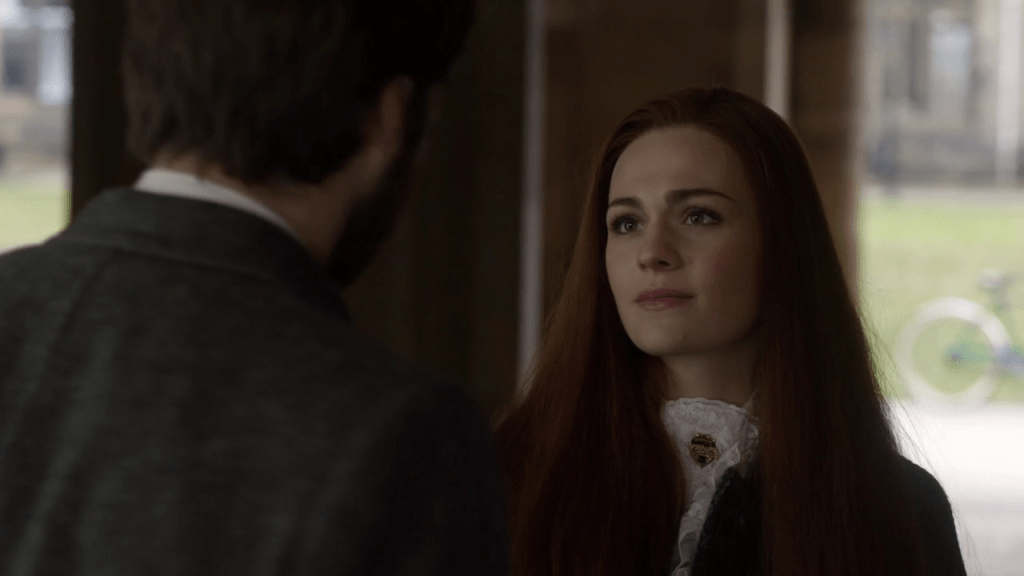

Photos: Outlander-Online, STARZ, Paramount Pictures

What a thought provoking piece! Thank you both!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was fascinating! The line: “Fiction was my entrance into history” particularly resonated with me. I was never interested in history growing up and by the time I went to college I decided that thought history should be taught through novels because if stories about PEOPLE could be told, more people like me would be interested. I can’t tell you how often while reading Outlander and other novels, I check up on the history (so happy my phone is next to me) to learn what is factual. And so much is, in Outlander. Now that I’m a family historian, I am consumed by the stories of my ancestors and kin, but with no written records, I have to make up their reasons for what they did. I wish I had the talent to write the fiction but historically based stories. Thanks to both of you for this.

LikeLike